Challenges and Problems in Brazil

Brazil Top Stories

Challenges and Problems in Brazil

“Social disparity, crime, taxes, bureaucracy…”; here are some of the challenges faced by Brazil, the sixth biggest economy in the world and the largest in Latin America. Can these challenges and problems affect the giant’s growth?

Challenges and Problems in Brazil

Although Brazil´s population totals close to 200 million people only 10% of them share almost half of Brazil´s national income, leaving the vast majority to subsist on government grants.

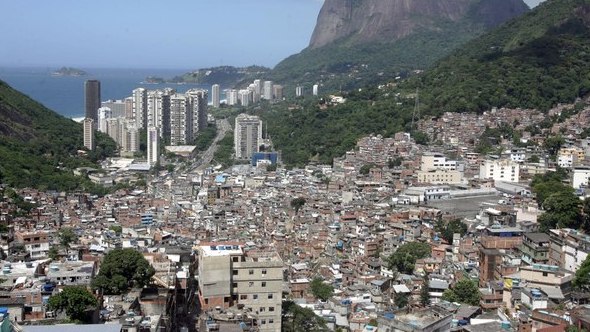

If you stand in the shadow of Rio de Janeiro´s iconic Christ statue you´ll be amazed by the beauty of the lush green jungle that extends down to the deep blue sea but also stunned by the millions of precarious shacks literally hanging off the hillsides above sprawling mansions sporting swimming pools and tennis courts. And whilst no other city in Brazil has Rio´s beauty, they all, to a greater or lesser extent, share its shocking disparity between rich and poor. Although Brazil´s population totals close to 200 million people only 10% of them share almost half of Brazil´s national income, leaving the vast majority to subsist on government grants, with a person in Rio´s posh seaside suburb of Leblon easily able to spend on dinner for two with wine what someone else in the city´s northern suburbs such as Belford Roxo earns a month. Although the gap has improved dramatically over the past 10 years and is continuing to improve in favour of the poor, as many government initiatives, especially during the Lula years (2003 – 2010), have pulled some 30 to 40 million people out of poverty and into a burgeoning middle class.

Closing the gap in this disparity has also helped the government to lessen crime and enabled it to turn its focus to security in the lead up to the Football World Cup to be played in various locations throughout Brazil in 2014 and the Olympic Games in Rio in 2016.

In order to cut down on both violent and petty crime, the government started by targeting drug traffickers and dealers who ruled the “morros” (literally hills) otherwise called “favelas” (slums). Called “pacification” this was initially done under the cover of night, sending in a special elite police squad known as the BOPE (pronounced Boppy in Portuguese and standing for Special Police Operations Battalion) to engage in high profile shoot outs with the drug lords. However as more and more innocent citizens were killed in cross fire and as the criminal factors within these communities saw how seriously the government was taking the issue of security, the “pacification” became more and more peaceful, with the police announcing where and when it was targeting, giving the drug dealers time to move out and let the BOPE enter without shots needing to be fired. After the initial phase of infiltrating these communities had been achieved a police force, known as the UPP, or Police Pacification Unit, was set up within them. The stated goal of Rio’s government is to install 40 UPPs by the start of the Football World Cup in 2014 and to date 28 have been successfully established.

These tactics have definitely reduce crime leading Mario Baptista, CEO of Protege – Brazil´s second largest company providing cash transit services – to state that “a lot of companies are worried about Brazil from a security point of view. I can understand where they’re coming from, as our image outside is one of crime. But when they get to know Brazil, they see that there’s not much to worry about.” Although in May 2012, José Mariano Beltrame, Secretary of Public Security for Rio de Janeiro, was forced to admit that armed criminals had “migrated from parts of Rio that have a large police presence due to pacification, to areas with less police and no UPPs” amid criticism that only the slums overlooking Rio´s more affluent suburbs had been pacified showing that the government was more concerned with boosting the city´s real estate prices and getting ready for key sporting events rather than the welfare of its citizens. A further criticism has been that safety alone is not enough and that the pacification program must be followed by adequate sanitation, health and education within these poorer communities.

And a less violent Brazil has also created other challenges, with real estate prices sky-rocketing in major cities. According to the Mercer Cost of Living worldwide ranking Brazil´s two largest cities feature in the Top 15 of the world´s most expensive cities to live in, with São Paulo ranking 12th and Rio de Janeiro 13th, in comparison New York which ranks in 33rd place. José Celso Gontijo, Director of JC Gontijo, the Federal District´s Largest Real-Estate Developer who also develops properties in other cities, stated in a recent interview that “In Rio de Janeiro, I’ve started building in Barra da Tijuca. There, the price per each m2 is R$ 10,000 ($USD 5,000). Also in Rio de Janeiro, I was made an offer of R$60 million ($USD 30 million) for a 700 m2 apartment. That’s an absurd price!” Although he did admit that “I think the prices have reached their peak.”

And it´s not just property that is overpriced as Brazil´s increasingly protectionist policies – such as the IPI (Industrialised Products Tax) introduced in 2011 – impose extremely high import taxes on goods, including for example a 30% tax on imported cars as opposed to just 16% in a country such as France. This has resulted in astronomically priced electronic goods, clothing and luxury foodstuffs prompting leading magazine Veja (Look) to run a cover story entitled: Why does Brazil have the most expensive iphone in the world? The cover featured one iphone with an American flag and the price $USD815 alongside another iphone sporting a Brazilian flag and the hefty price tag of $USD1650. Brazil also has the second most expensive Big Mac in the world. Whilst this strategy is working for the government itself, forcing citizens to buy domestically produced goods and thus keeping the local market strong, it is at the same time condemning the average wage earner to having to buy cheap, inferior quality Brazilian-made products.

A further challenge that Brazil must overcome if it truly wants to be considered a new super power is its lack of infrastructure. Labelled as “deficient” by Economist reporter Michael Reid, it was recently highlighted on economist.com in an article entitled “The road forsaken” that only “14% of roads are paved” and that “The World Economic Forum ranks Brazil’s quality of infrastructure 104th out of 142 countries surveyed”. On a more positive note however, with President Dilma having announced a new “Logistics Investment Package” opening bidding to private companies for concessions to build and operate the country´s motorways and railroads, the Economist´s Brazilian Bureau Chief Helen Joyce, has signalled that investment opportunities in Brazil´s infrastructure should be seen as “low hanging fruit” meaning Brazil is ripe for the picking for an international company looking to invest in the developing world, as long as it has the patience to deal with the inevitable red tape and bureaucracy for which Brazil is infamous.

According to the 2012 annual global report on “Doing Business” published by the World Bank, set up to evaluate just how easy, or not, it is to start up a business in any given country, Brazil ranks 126th out of 183 countries. Whilst it´s not a good sign for the world´s sixth-largest economy and it certainly doesn´t help President Dilma´s bid to woo foreign investment things are at least improving with foreigners now being able to open their own entirely independent businesses whereas in the past a Brazilian business partner was required. In an article on the BBC´s website entitled “Brazil´s business labyrinth of bureaucracy”, it was revealed that it takes “13 procedures and 119 days of work to start a business in Brazil” whilst getting a permit for building can take up to “17 procedures and 469 days to finally get authorised” leading Joao Carlos Gomes, economy superintendent at the Trade Federation of the State of Rio de Janeiro, to admit: “It’s crucial to make Brazil meet the global standards. We’re very far away from it.” All this red tape however is not detracting from Brazil´s attractiveness as a country in which to invest with Louis Bazire, President of the French-Brazilian Chamber of Commerce stating that despite a “strong bureaucratic mentality” there were “60% more companies coming to see us last year compared to the year before, so there must be something else in Brazil that attracts them to come here. For instance, it can be the potential of 200 million consumers and the fact that in the last ten years, 30 to 40 million citizens came out of poverty and had access to consumption, which created a strong dynamic of the Brazilian company. Secondly, institutions are quite stable in Brazil. What’s more, there have not been any major issues with the recent political changes. This is very important for someone who invests.”

In terms of investing in its own future an absence of decent public education must be put on the government´s agenda as a major problem to be resolved, as a lack of teachers and a shortage of classrooms has led to a huge gap between the quality of private and public education in Brazil and the government´s tax on training makes businesses less willing to invest in development programs for its employees. Ozires Silva, Rector of Unimonte and Founder of Embraer, recently spoke about the fight to get the Brazilian government to amend legislation saying “we made a proposal in order to replace tax over the schools by incentives. In Brazil, schools are taxed and the private schools must collect taxes directly from the payments of students. Most of the graduate students are in private institutions and surely that is not acceptable” adding that “whenever companies do training for employees, the government charges the company.” When asked what could happen if Brazil does not address this problem Silva explained that “competitors are global… the competition in the world is regarding high competence and knowledge” confirming that “Brazil will surely have very serious economical and social problems in the future” if it fails to improve its education system at all levels.

Talking about all of Brazil´s problems and challenges, Luis Fernando Furlan, former Minister of Development, Industry and Foreign Trade, stated “compared to other countries, I see Brazil as running a marathon. Our country is running a marathon with a backpack full of stones that reduces our competitiveness. These stones represent bureaucracy, infrastructure, education, high interest rates, the tax burden and corruption. However, as long as we are finding solutions, we can throw away these stones and become lighter and compete better in the marathon.” And with President Dilma paving the way towards greater political transparency, if Brazil can take tackle these problems with the same focus and commitment that it has shown when dealing with poverty and crime then moving forward Brazilians, foreign investors and tourists alike should all be able to enjoy more of Brazil´s beauty and less of its bureaucracy.