Inside lraq’s Cash Economy: Fully Reserved Banking in a Monetary Dystopia

As is the case in many conflict and post-conflict economies, in Iraq the private sector is primarily cash-based. Bank financing is unavailable for all but the largest companies and even then is limited mainly to overdraft facilities.

By Dr. Mark A. DeWeaver

As is the case in many conflict and post-conflict economies, in Iraq the private sector is primarily cash-based. Bank financing is unavailable for all but the largest companies and even then is limited mainly to overdraft facilities. While checks are often used for payments between businesses within the same city, cash transfers—via the movement of physical cash or through money transfer companies—dominate the payments system. The majority of households do not even have a bank account. Those with savings often hold them in the form of US dollar hoards in private safes.

This state of affairs places significant limitations on the financial system because it practically rules out fractional reserve banking. The business model for Iraqi institutions is necessarily quite different from that of banks in developed countries, which generally hold only a small share of their deposit base as reserves in the form of vault cash and reserve accounts at the central bank. Most of their deposits are available to be lent out. This is possible because depositors are likely to withdraw only a small fraction of these funds on any particular day.

The private banks and money transfer companies that serve Iraq’s cash economy cannot really operate in this way. The former are subject, both individually and collectively, to large and unpredictable demands for cash from depositors; the latter do not take deposits at all.

As a result, Iraq’s financial system has become a dystopic realization of the fully reserved banking schemes that Austrian economists have proposed as a means of eliminating boom-bust investment cycles.1 It bears a surprising resemblance, for example, to Huerta de Soto’s “ideal model for the financial system of a truly free society,” where there would be one hundred percent reserve backing for deposits, free (i.e. unregulated) banking, and freedom of choice in currency.

While not all Iraqi privately owned banks hold one hundred percent of their deposits in cash, those listed on the Iraq Stock Exchange (ISX) had a combined cash-deposit ratio of 97% at the end of 2014, an extraordinarily high figure in comparison to their international peers. System-wide, the combination of money transfer companies and cash in private safes is essentially a parallel fully reserved banking system in which different entities are responsible for custody and payments functions. The money transfer companies also approach the ideal of free banking in that they are only lightly regulated and are disciplined mainly by reputational incentives. Finally, the partial dollarization of the economy affords Iraqis considerable freedom of choice in currency.

An important implication of one hundred percent deposit reserves is that demand deposits are not available to finance loans, which must instead be covered by bank capital. For Austrians, this is desirable because it precludes the possibility that money creation by the banks will lead to credit-fueled investment booms, which in fact is not a problem in Iraq. Iraqi episodes of overinvestment have been primarily the result of high oil prices rather than excess credit.2 It is not really the case, as Iraqis sometimes complain, that funds in fully reserved accounts or private safes are somehow unavailable to the “real” economy.

Regardless of the form it takes, money does not literally “flow” into physical goods. Trade and investment do not transform the medium of exchange into commodities; they simply transfer it from buyers to sellers. Cash plays the same role in the payments system regardless of whether or not it available to be lent out. It is never “sitting idle.”

What makes Iraq a dystopia, rather than the monetary utopia that Huerta de Soto and other Austrian economists have in mind, is the absence of the rule of law. The lack of effective bank supervision means depositors cannot be sure that their funds are safe, which naturally makes it difficult for banks to act as custodians. In an environment where armed robbery is an everyday occurrence, there are high transaction costs associated with guarding and transporting cash. Without reliable contract enforcement it is also impossible for financial intermediation to take place through pooled investment funds, which Austrians argue could substitute for bank lending in a fully-reserved system.

Instead, medium and long-term financing must largely be limited to parties that know each other personally. While Heurta de Soto’s proposal might conceivably be optimal in a country with strong legal and regulatory institutions, the Iraqi version is merely a last resort. It is the best that can be achieved through “private orderings” in the absence of reliable public governance.

The remainder of this paper shows how fully reserved banking has become the norm in Iraq’s private sector and explores some of the implications for policy making. Section I explains why Iraqi private sector banks tend to hold much higher levels of deposit reserves than their developed country counterparts despite the lack of any official requirement for full reserve backing. Section II demonstrates how money transfer companies make it possible for privately-held cash to take over the role that deposits normally play in the payments system, thereby allowing stashes of banknotes to serve as a kind of “homemade reserves.” Section III looks at the central bank and explains why conventional monetary policy, prudential supervision, and anti-money laundering regulations are generally ineffective or counterproductive under Iraqi conditions. Finally, Section IV concludes with a “second-best” argument for the Austrian “ideal model.”

I. Fully Reserved Banking as a Last Resort

While the Central Bank of Iraq (CBI) requires private banks to hold 15% of their deposits as reserves, most hold well over 50%. Unlike foreign lenders, cash and equivalents rather than loans are the Iraqi private banks’ single biggest asset. They have the dubious distinction of being among the most liquid financial institutions in world.

Consider the six ISX-listed banks that had foreign banks as major shareholders as of the end of 2014 (see Figure 1). Cash-deposit ratios ranged from 9% to 28% for the parents compared to 49% to 121% for the subsidiaries, whose combined cash assets covered 86% of deposits. For the locally controlled listed banks, the corresponding figure was even higher at 105%.

Iraqi bank managers will tell you that they need cash to meet unexpected large withdrawals by depositors. But this is true of banks everywhere. Why should Iraqi lenders be so much more liquid than their counterparts in other countries?

Their behavior does not seem so strange when you consider the fact that Iraq lacks a functioning interbank market. Ordinarily/ banks with a cash shortfall at the end of the day can borrow overnight from those with a surplus. As long as the public’s demand for banknotes is unchanged, withdrawals from bank ‘A’ end up as deposits at bank ‘B’, ensuring that ‘A”s demand for short-term money can usually be easily met.

In Iraq, a bank that ended up with a cash shortfall would in theory be forced to borrow from the CBI. This is a much less attractive alternative than borrowing from another commercial bank, however, and reportedly almost never happens in practice.

Institutions in developed countries that are perceived to be in trouble may still be able to access funds in the interbank market provided that they are willing to pay a high enough interest rate. The central bank, however, is both lender and regulator. It is not going to provide liquidity to the highest bidder, regardless of the circumstances. This is particularly true of the CBI, which lacks the strong oversight powers of monetary authorities in other countries. It could quite easily be taken advantage of by the commercial banks if it were to get a reputation for being a “soft touch.”

Of course all of this begs the question of why there is no interbank market in the first place. Couldn’t the central bank simply set up a system through which banks could make short-term loans to one another? The problem seems to be partly a result of the dominant role of the state banks, which together account for the vast majority of system-wide deposits. Without their participation, an interbank market would not work. There would be no guarantee that at the end of a given day the private banks collectively would not end up with a cash deficit while the state banks had a surplus. In a market where only the private banks participated, those with extra funds might not have enough to meet the demand of those with a shortfall.

So why not get the state banks involved? Unfortunately, that would not be ideal either. Like state-owned enterprises in general, these banks can always count on a bail-out if they get into trouble. This means that as interbank lenders they would be likely to act recklessly, making funds available to anyone willing to pay a high enough interest rate, regardless of counterparty risk. The inevitable result would be an increase in the state banks’ non-performing loan ratios and a corresponding hit to the government budget.

There also can be no presumption that all of the cash withdrawn on a particular day would return to the banking system as new deposits. Much of the outflow might instead be hidden in people’s homes. This might be the case, for example, during a crisis such as the Islamic State’s takeover of northwestern Iraq in the summer of 2014. As long as the security situation is unstable, the banks will have to be prepared to meet sudden and unpredictable spikes in withdrawals at a moment’s notice.

The need to hold large amounts of vault cash and central bank reserves naturally implies that the private banks’ main business cannot be medium or long-term lending. Their activities are instead largely limited to foreign exchange trading, money transfers, and the provision of overdraft facilities, letters of credit for importers, and performance bonds for construction contractors. As would be true of the fully reserved banks imagined by Austrian economists, loans seldom exceed shareholders’ equity.

In most countries, any bank holding over half of its deposits in cash would appear to be incredibly badly run. In Iraq, the reverse is more likely to be the case. Banks with low cash levels may be at risk of failing. Warka Bank, one of Iraq’s worst bank failures in recent years, is a case in point. Once ranked flrst among the listed banks in terms of total assets, Warka was taken over by the central bank and delisted from the stock exchange in 2011. By the end of the second quarter of 2010, its cash¬deposit ratio had fallen from 79% as of year-end 2009 to 12%—not a particularly alarming level by international standards but fatal in Iraq. By the second quarter of 2011, when the bank last published its flnancials, the ratio had fallen to a mere 1%.

II. Money Transfer Companies and “Homemade Reserves”

Money transfer companies (MTCs), known as hawalas in Arabic, play a key role in transferring funds among Iraqi cities and internationally. Their proflts are generated almost entirely by money transfers and foreign exchange trading. Some hardly use banks at all, keeping most or all of their funds in cash. Others have relationships with the larger local financial institutions, as well as those with whom their major shareholders have personal connections.

These companies tend to be concentrated in bazaars, where they occupy modest premises often containing little more than a counter, safe, money counting machine, a few chairs and a table. While outwardly unimpressive and largely operating outside the formal financial system, they are participants in an extraordinarily complex global financial network with many similarities to those used to process commercial bank transactions. Average daily volume at even medium-sized outlets in Sulaimani is reportedly well over one million US dollars.

Contrary to popular belief, money transfers do not involve any movement of physical cash. When the sender gives a sum of cash to MTC yA’, ‘A’ simply instructs a correspondent in another city, call it MTC /B/, to deliver that amount to the recipient, who is given a password and must also present some form of identification. The money does not y/goyy anywhere—/A/ simply ends up with an increase in its cash balance, and yB’ with a decrease.

Studies of international MTC remittances such as Passas (2003), Schaeffer (2008), and Maimbo (2013) tend to focus on the role of the transportation of physical cash or tradable goods or the transfer of funds between bank deposits in effecting settlements among the MTCs themselves. Our informants in the Sulaimani bazaar, however, indicated that the majority of their outstanding balances are not settled in this way, but rather through a book-entry process.

In the simplest case, the imbalance between the sender and the receiver might be reversed through a subsequent transfer in the opposite direction. If /B/ later transfers money to ‘A’, /B//s deficit could be eliminated when it receives cash from its customer, while yA”s surplus might disappear when it pays the recipient.

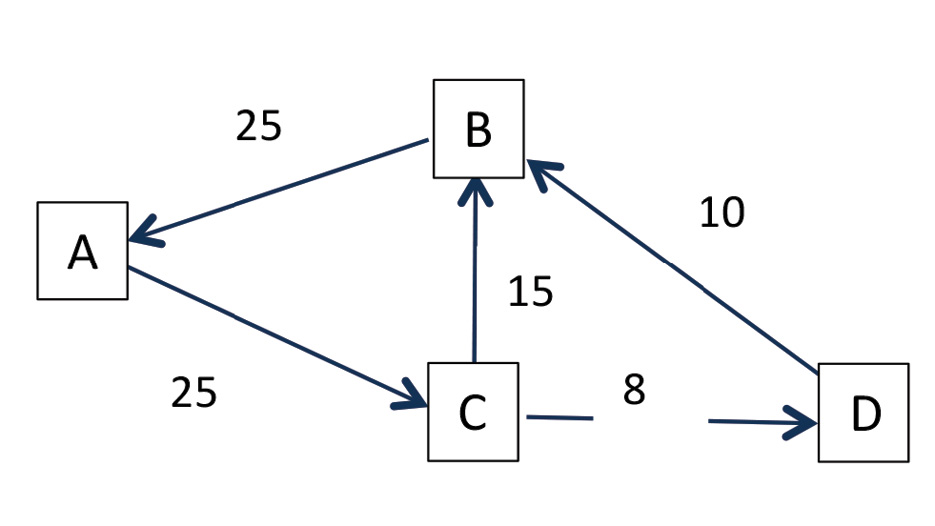

Naturally incoming and outgoing transfers will rarely exactly offset each other in this way. In a more realistic case, settlement among MTCs will involve multiple parties. Suppose yB’ owes yA’ $25 following net transfers from ‘B’ to yA’ totaling this amount. At the same time, perhaps yCy and yD’ owe $15 and $10 to yB’, respectively, yCy owes yD’ $8, and yA’ owes $25 to yCy (See Figure 2). Settlement among these four MTCs could start with the following:

1. yA’ cancels its $25 credit with /B/.

2. ‘B’ cancels its $15 and $10 credits with ‘Cy and yD’.

3. yD’ cancels its $8 credit with ‘Cy.

4. ‘Cy cancels its $25 credit with /A/.

It is easy to see how this works if we consider the effect on each MTC separately:

1. ‘A’ no longer owes $25 to ‘C’ and no longer has a $25 receivable from ‘B’.

2. ‘B’ no longer owes A’ $25 and no longer has a combined total of $15 + $10= $25 in receivables from ‘C’ and ‘D’.

3. ‘C’ no longer owes ‘B’ and ‘D’ a combined total of $15 + $8 = $23 and no longer has a $25 receivable from A’. ‘C’ thus ends up with a $25 -$23 = $2

credit balance vis a vis the system as a whole, which could be eliminated through a payment from ‘D’.

4. ‘D’ no longer owes ‘B’ $10 and no longer has an $8 receivable from ‘C’, ending up with a $10 – $8 = $2 debit balance, which could be eliminated by a payment to ‘C’.

Through those operations, system-wide obligations totaling $83 have been reduced to only $2 -the remaining imbalance between ‘C’ and ‘D’.

In the Sulaimani bazaar -and presumably in similar venues elsewhere in Iraq – arrangements like these are made directly among correspondents or may be facilitated through the intervention of brokers that bring together MTCs with complementary imbalances. These intermediaries do not hold cash themselves but work for a share of the commissions associated with the transfers they help to settle. Our informants had not heard of any companies using their own capital to consolidate MTC debits and credits.4

For MTCs like ‘A’ and ‘B’ that start with equal credit and debit balances, settlement is solely a matter of making offsetting accounting entries. The possibility of physical settlement only arises in cases like those of ‘C’ and ‘D’, where the MTCs initially have non-zero net balances. Even then it is often not necessary.

MTCs often hold small balances with each other/ which makes it possible for the book- entry settlement process to be completed over more than a single period. To ensure that this happens in a timely fashion, a common strategy for those with debit balances is to reduce or suspend transfers to their counterparties with the corresponding credits. This can be achieved by raising the commission rate on outgoing transfers or even temporarily refusing them altogether. Similarly, the party with a credit balance can reduce its rate or even waive it entirely to stimulate outgoing transfers. Over time, the imbalance will be reduced to zero as the debtor pays out cash to the beneficiaries of the creditor’s incoming transactions.

The ability to control their transactions volume, means that the MTCs have considerably more control over their cash flows than banks, which must pay out funds to depositors on demand regardless of the size of the required net withdrawals. MTCs do not face the same uncertainty—if they do not have enough cash on hand they do not have to accept incoming transfers. They might lose business and credibility as a result, but are at least not at risk of bank runs.

Our informants reported that settlement is typically daily in the case of correspondents in major cities, and weekly for those in smaller cities with lower transaction volumes. Their network of correspondents is international in scope. Even balances among local counterparties may be settled in regional centers such as Dubai and Istanbul, or sometimes as far afield as Shanghai and Beijing.

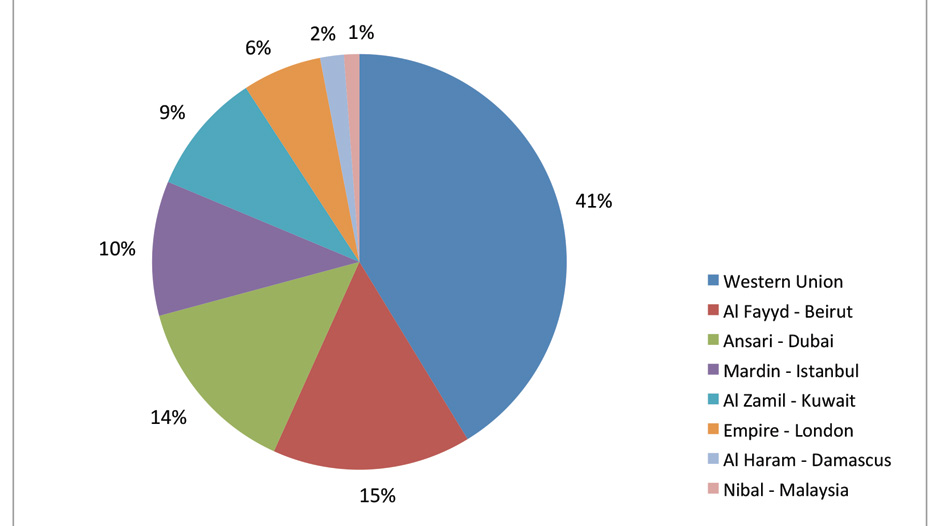

We can get an idea of the relative importance of some of these overseas network nodes from the 2014 annual report of United Arab Money Transfer (MTUA), the fourth largest of the fourteen ISX-listed MTCs in terms of revenue. Figure 3 shows receivables due from eight foreign correspondents, which together account for 39% of total receivables.5

As one might expect, MTCs based in regional financial centers have the biggest shares after Western Union, which has a large operation in Iraq. Its website lists 75 Iraqi outlets, ofwhich eight are MTUA branches in Baghdad.

MTCs resemble banks not only as operators of a payments system but also as providers of short-term credit. Not only are they effectively making loans to the counterparties with which they have outstanding credit balances, they may also fund outgoing transfers for well-known clients—a service much like a bank overdraft facility. One MTC in the Sulaimani bazaar told us it can cover anywhere from 10% to 100% of the transfer amount interest free, without collateral, for periods of up to ten days.

The main difference between MTCs and banks is that the former do not accept deposits and typically also do not hold cash balances as pre-funding for anticipated future transactions. The bank’s normal custody role is essentially outsourced to the client himself, who only relinquishes control of cash when making a transfer.

We might think of all of the MTCs’ clients’ collectively as holding a “homemade” one hundred percent deposit reserve. Combining this with the MTCs’ services results in what is perhaps the most basic form that a banking system could take. While obviously not an optimal arrangement for most economies, it is one of the outstanding success stories of the Iraqi private sector—a means of keeping economic activity from collapsing in an environment with few effective legal safeguards or government regulations.

III. Implications for Monetary Policy and Bank Supervision

Fully reserved banking has important implications for the conduct of monetary policy and bank supervision. In Iraq, most of the tools available to central banks and regulators in other countries are inappropriate or ineffective. In some cases, their application may in fact do more harm than good.

Consider interest rate policy, for example. In a country with a well-developed banking sector, raising rates can slow economic growth by creating a disincentive for individuals and companies to borrow. Cutting rates has the opposite effect. In Iraq, such measures make little difference because there is so little private-sector lending. They also do not matter much to the state sector, where the lack of hard budget constraints means that lending decisions are generally not going to be particularly interest-rate sensitive.

The same ¡s true of changes to the required deposit reserve rate-one of the central bank’s most potent weapons in many developing countries. For banks whose deposits are almost fully covered by cash and reserves, moves like the CBI’s last reserve-rate cut—from 20% to 15% effective September 1, 2010—must invariably be non-events.

In Iraq the only really effective means of controlling the money supply is through the exchange rate, because money creation results primarily from the central bank’s conversion of US dollars from government oil exports into local currency. If the CBI raises the IQD/USD exchange rate, it will create more dinars for each dollar it buys from the government. If it lowers the rate, money-supply growth will slow.

Since exchange rate stability is one of the CBI’s main objectives, however, its use of the exchange rate for macro-economic management has been limited. Instead, the price of oil has become the main driver of the Iraqi money supply. When the oil price rises, the Ministry of Finance has more dollars to exchange with the central bank. If the exchange rate is unchanged, more dinars will have to be created to purchase them and the money supply will increase. An oil price drop has the opposite effect.

Prudential supervision based on bank-capital ratios, is also inappropriate in the Iraqi context. For banks with large loan books, capital adequacy ratios (e.g tier-one capital to risk assets) are important because they measure a bank’s ability to cover losses from bad loans. In Iraq, such ratios are not really relevant—the denominator may be close to zero. Given that liquidity risk, rather than credit risk, is the key issue, cash-to-deposits is clearly the best indicator for regulators to monitor.

The CBI’s policy on bank and MTC capital is based on absolute capital levels. All private banks were required to raise capital to IQD 100 billion by the middle of 2011, IQD 150 billion by the middle of 2012, and to IQD 250 billion by the middle of 2013, for example. Similarly, the CBI recently required the MTCs to raise capital to IQD 45 billion. It is not clear how these policies can be justified on prudential grounds. They seem rather to be an attempt to force the banks to lend more, coerce the smaller banks into merging with one another (this has not happened), and reduce the number of MTCs.

In some cases, the CBI’s insistence on capital increases also appears to have led to increases in the quantity of capital at the expense of quality. Some majority shareholders are said to have used personal lines of credit from their banks to pay for their own rights-issue shares. The problem with this, of course, is that if those shareholders are unable to repay their loans, the banks will take a loss and the new capital will have to be written off.

Similarly, the CBI’s anti-money laundering (AML) policies have sometimes had unintended consequences. In 2012, for example, the central bank introduced new regulations requiring anyone purchasing dollars at its official rate to provide documentary evidence of the purpose for which the foreign exchange would be used. Rather than blocking illicit currency flows to Iran and Syria, the new rules instead produced a market for Iraqi government-certifled manifests, which could be used to prove the existence of a legitimate transaction. The policy did little more than create an opportunity for officials with access to the right government seals to make a quick profit stamping phony documents.

It is doubtful, in any case, that AML can be effective in the Iraqi cash economy. Requiring banks to follow AML best practice when sending bank wires, for example, leads not only terrorists but ordinary people to use MTCs instead. Dealing with a bank’s required documentation is simply too time-consuming. Nor would it make sense to crack down on MTCs. They are not going to be in a position to satisfy “know-your-customer” requirements for clients whose transactions are entirely in cash and therefore leave little if any paper trail.

IV. Conclusion

In developed countries, the use of cash for all but the smallest transactions has become increasingly suspect. In the US, anyone trying to make a large purchase using hundred dollar bills would probably be assumed to be a criminal. Most of the foreign media coverage of money transfer companies focuses on their role as financers of terrorism. There have recently even been calls for the elimination of large denomination bills such as the 100 US dollar and 500 Euro notes (New York Times, 2016).

Understanding Iraq’s monetary dystopia allows us to see cash in a more positive light. In cases where legal remedies and government regulations are ineffective, the cash economy is not primarily a haunt of terrorists and drug smugglers. It is rather the setting for most ordinary private-sector activity. The only alternative would be reversion to a barter economy.

The absence of fractional reserve banking in Iraq is not the fault of banks and MTCs or their customers. It is rather a natural consequence of the dominant role of banknotes as a means of exchange and a store of value. Forcing these companies to raise capital, insisting that they implement Western-style money-laundering procedures, or otherwise attempting to convert them into “real banks” will not change the way they do business. Without any improvement in the effectiveness of state institutions, private-sector actors will continue to rely primarily on cash. Changing the current fully reserved system will inevitably prove to be an illusory goal.

Naturally none of this is evidence either for or against the position that one hundred percent reserve banking would be optimal in developed economies. The point is rather that in countries like Iraq this system may be the only one that will work. Its advantage in this context is not the amelioration of the business cycle, as would be the case in an Austrian monetary utopia, but rather the protection of private wealth in highly uncertain and often lawless environments.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Hakar Elias and Sara Al-Nesany for their help as research assistants, as well as Christine van den Toorn and Zeina Najjar of the AUI-S Institute for Regional and International Studies (IRIS), without whose support this report could not have been written. The following people also made significant contributions to the analysis and information included: Awatif Raheem (Al Mansour Bank), Blend Hikmat (American University of Iraq), Eric DeWeaver (National Science Foundation), Hawkar Ismail (Hawkary Kurdistan), Jean Bassil (Byblos Bank), Mahdi Akram (Rabee Securities), Qusay Razzaq (Euphrates Fund), Rami Yassir (Rabee Securities), Rawaz Rauf (Fanoos Telecom), Shwan Taha (Rabee Securities), and staff members of Faraidoon for Money Transfer and Exchange, who would prefer to remain anonymous.