FACES OF THE ECONOMY: Ziad Kamel

Faces of Economy – Lebanon

FACES OF THE ECONOMY: Ziad Kamel

There are 1.4 million workers in Lebanon – this is the story of one of them.

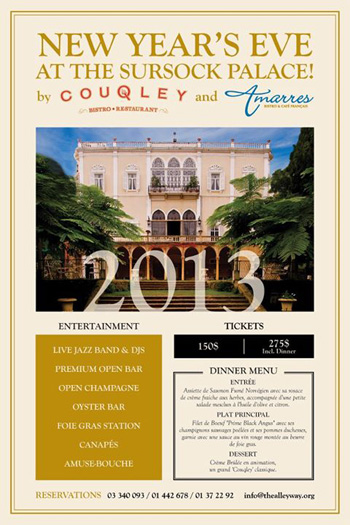

On January 1st 2005, a 24-year-old Ziad Kamel woke up the night after hosting yet another successful New Years Eve party for several hundred guest at Sursock Palace in Beirut. And with the New Year came a new adventure for the young entrepreneur.

FACES OF THE ECONOMY: Ziad Kamel

There are 1.4 million workers in Lebanon – this is the story of one of them.

By Justin Salhani

BEIRUT, Lebanon – On January 1st 2005, a 24-year-old Ziad Kamel woke up the night after hosting yet another successful New Years Eve party for several hundred guest at Sursock Palace in Beirut. And with the New Year came a new adventure for the young entrepreneur.

“At that time, I was working in the ad sector but had bigger goals,” said Kamel, now the Treasurer of the Syndicate of Owners of Restaurants and a business owner, from his office in Gemmayze. After the success of his parties, Kamel wanted to experience that feeling everyday by being his own boss with his own company.

Determined to achieve his dreams, the business administration graduate from the American University of Beirut with a masters from the University of Surrey got to work planning his future. He had an idea to open an establishment in the “then unknown neighborhood Gemmayze” he said. But obstacles quickly piled up along the way.

“One month later they blew up [former Prime Minister Rafik] al-Hariri,” said Kamel. The assassination of arguably the foremost political figure in Lebanon led to daily protests and was also the jump-off point for a wave of political assassinations that took the lives of many Lebanese politicians and journalists.

But Kamel was undeterred. “I didn’t listen to anyone and I convinced my father to secure a bank loan as a guarantor. In May 2005, we legally rented two locations in what is now the Alleyway. At the time it was an old destroyed area.”

The plan for Kamel and his business partner Paddy Cochrane was to take two venues at the same time. “It cost less and we could try two different concepts while at the same time protecting our businesses from competition,” Kamel said.

“I naively though we could open in three months but it took ten just to secure licenses,” he said, adding that he frequented the local municipality for a couple hours a day three times a week before going to his day job at Leo Burnett.

Gauche Caviar, a bar, was launched on July 8, 2006. “We were the happiest business owners in the world,” said Kamel. “The first three days were amazing and packed until July 12. That’s when Israel bombed the hell out of Lebanon.”

A distraught Kamel sent his staff home, packed everything he owned into a gym bag, and joined his family in a “dodgy taxi ride” that took him from Beirut to Damascus then on to Amman before he would board a flight to Kuwait.

“I went from hero to zero in 24 hours,” he said. Kamel also feared that this conflict would drag on for longer than expected.

“Everyone said the war would last a few days but the elders reminded us that the same was said about the civil war and that lasted 15 years.”

“I didn’t listen to anyone and I convinced my father to secure a bank loan as a guarantor. In May 2005, we legally rented two locations in what is now the Alleyway. At the time it was an old destroyed area.”

Still, Kamel boarded the first flight from Kuwait back to Beirut and re-launched a “ceasefire party” on August 24, 2006. “The situation got better and sort of revived. The GCC pushed its nationals to spend here and the entire sector benefitted. We opened our second establishment Cloud 9.”

But the security situation still affected business. In May 2007, Lebanon saw its most severe battle take place in the northern refugee camp of Nahr al-Bared. Beirut was affected by bombings and people tried their best to stay off the streets.

Throughout these struggles, Kamel realized he had two options. “We either leave or stay and put up with this like it’s a natural disaster season,” he said.

The existential crisis didn’t last and Kamel’s company opened a clothing store, a tanning salon, Couqley restaurant and the two bars. He also resigned from Leo Burnett to focus full time on his business. Despite the hardships, Kamel maintains that fortune had blessed them in a couple of instances. “Gemmayze was the only place to go out at that time,” he said, implying that there was little competition from other areas that have since blossomed with nightlife like Hamra, Monot, Jounieh, Jbeil and others.

Kamel summarizes his management philosophy with a few key words: integrity, communication, fairness, quality, training, empowerment, and humility.

“In my own company, which employs more than 50 people, I have tried my best to change the stereotypes about what the ‘moudir’ should and shouldn’t do. So far it has worked and has been one of the main reasons why my company remains successful after founding it 8 years ago. Contrary to what some of my employees have been used to by working in companies before joining mine, I strongly believe in creating happy customers via training. In our industry, happy employees = happy customers = better performance,” Kamel wrote via email.

The next few years went well for Kamel and co. They even felt confident enough to launch a restaurant, Amarres, in Beirut’s tourist trove Zaitunay Bay. But it wasn’t to last.

“In 2010 the economy started curving off then 2011 was the start of the problems in Syria,” he said, referring to the armed conflict in Syria that has deeply affected Lebanon’s economy and money making industries such as tourism.

“Since 2010, each year has been worst than the last,” Kamel said, adding that 2012 was the biggest challenge. “We already had expanded and there wasn’t enough business to meet our demands.”

And in March of 2012, the GCC encouraged their nationals not to visit Lebanon. Kamel was forced to close Amarres, since it heavily relied on Lebanese expats and foreign tourists that just weren’t coming to Lebanon.

With Syria seeing no end in sight and security incidents in Lebanon becoming more of a regularity, Kamel’s younger bullishness has evolved toward what could be described as a more mature pragmatism. And while his optimism toward business hasn’t diminished, he is pessimistic in regards to Lebanon’s ability to maintain stability to allow businesses like his to flourish.

“There is no end in sight,” he said. “Personally, I don’t see [the security situation] getting sorted for years.”

Gauche Caviar has closed, though it will reopen next year Kamel hopes. Cloud 9, now named the Angry Monkey, has closed for the summer season as “people want to be in the mountains, on the beach or at the rooftop clubs” and will reopen in the fall of this year.

But despite scaling back, Kamel has found order in the chaos that is Lebanon and launched a second chain of his successful restaurant Couqley in the area of Dbayeh, north of Beirut, off the autostrade.

“I understood the crisis and now we are targeting Lebanese who live and work in Lebanon,” he said. “Dbayeh is a non touristic area where you find locals and not a lot of expats or tourists.”

“Mount Lebanon is mostly peaceful and stable,” said Kamel, adding that the rule of law is applied there, at least relatively, compared to Beirut, Sidon, the Bekaa Valley and Tripoli.

Kamel says it’s too early to tell if the business is a success but the first two months have gone well. A businesses novelty period usually lasts between two to four months.

But apart from re-launching the two bars, Couqley’s second branch will be Kamel’s last investment in Lebanon for the time being.

“The next market is the GCC,” he said, adding that he hopes to open a branch of Couqley in Dubai and Abu Dhabi before continuing on around the region.

“If I do what I did here in Dubai is something I think about a lot and I want to find out.” He says it shouldn’t be hard to resettle in Dubai as his family has already agreed and his network there is extensive. Kamel is married with two children, a 3-year-old daughter and a 3-month-old son.

“Everyone I knew here is over there now.” And he is optimistic about his chance at success in Dubai.

“Doing this here won’t make you rich, even in peace because the market is small. You could eventually succeed but to go abroad is quicker.”

Although he is prepared to leave Lebanon in the next year or so, he is still hopeful that one day he can return to a peace and stable country.

“Ideally, I would have stable a Lebanon with a strong economy and tourism sector. If that were the case I would invest everything to make a better country. I would actively campaign for expats to come back, because Lebanon is a sleeping giant and it’s fun. But for now in Lebanon you feel you can’t improve. When you have no help from the government you can’t do anything.”

Justin Salhani is the Lebanon Correspondent for The Atlantic Post, a Washington DC based startup, and a freelance correspondent based out of Beirut. He covers politics, security, and culture. He can be reached by email at jsalhani@theatlanticpost.com or on Twitter @JustinSalhani.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Every two weeks Marcopolis will profile a different hardworking citizen. Nominations can be sent by you, friends, family or even coworkers, for inclusion in the “Face” series. Tell us your story. Send to contributing business correspondent: T.K, Maloy: tkmaloy@gmail.com