History of Côte d’Ivoire

The modern history of Ivorian independence begins with the dynamic personality and leadership of Felix Houphouët Boigny (pronounced Feliks Oufwet Bwajni) (1905-1993)

Côte d’Ivoire has a rich pre-colonial history. Five major native states flourished in the pre-European era: (1) the Muslim Kong Empire; (2) the Abron kingdom of Gyaaman; (3) the Baoule kingdom at Sakasso; and two Agni kingdoms: Indénie and Sawwi.

History of Côte d’Ivoire

Brief History of Côte d’Ivoire

Côte d’Ivoire has a rich pre-colonial history. Five major native states flourished in the pre-European era: (1) the Muslim Kong Empire; (2) the Abron kingdom of Gyaaman; (3) the Baoule kingdom at Sakasso; and two Agni kingdoms: Indénie and Sawwi.

The Portuguese explored the coast in 1482, but did not establish a colony. Because of its strong native kingdoms, Côte d’Ivoire did not figure much in the slave trade.

A small French settlement was established in 1637. It was not until 1843, however, that France, began to move beyond the this settlement to enter into treaties with local West African rulers, which enabled them to build fortified posts along the coast that could become permanent trading centers.

In the mid-1880s France began to explore and expand its influence into the interior. In 1887, French officers secured nine treaties with native tribes that extended French influence inland. In 1893, Côte d’Ivoire was formally declared a French colony.

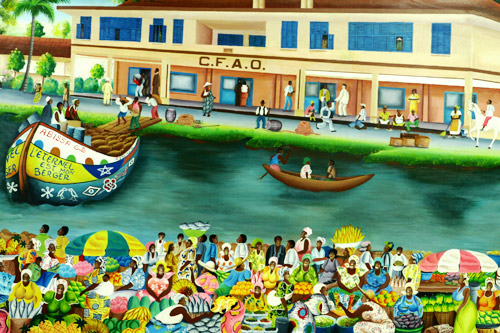

The declared pillars of French colonial policy aimed at assimilation and association. As a result, Côte d’Ivoire attracted more settlers than any other West African colony, whether French or not. The settlers’ main goal was to increase exports by expanding the planting of coffee, cocoa, and palms for palm oil.

After World War II, the policy of assimilation was strengthened to grant French citizenship to all former African subjects, and the right to organize themselves politically was recognized. For the first decade of so after the war, most Ivorian leaders believed that the best route was to assimilate with France, largely because being a French possession carried with it immense economic advantages.

By the mid-1950s, however, most Ivorians concluded that equality could only be achieved by independence.

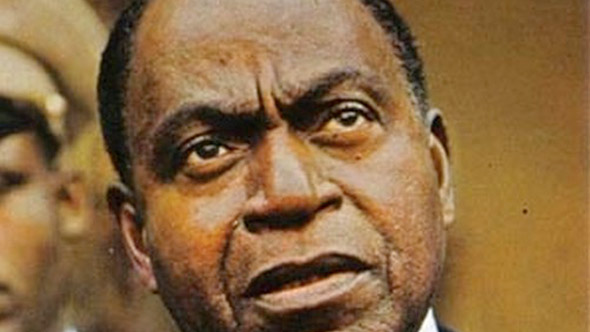

Felix Houphouët Boigny—the “Father of Côte d’Ivoire’s Independence”, “Grand Old Man”, and “Sage of Africa”

The modern history of Ivorian independence begins with the dynamic personality and leadership of Felix Houphouët Boigny (pronounced Feliks Oufwet Bwajni) (1905-1993) who was a major leader in Ivorian politics from the 1940s. He led the country to independence, and served as its first president from 1960 to his death in 1993.

The modern history of Ivorian independence begins with the dynamic personality and leadership of Felix Houphouët Boigny (pronounced Feliks Oufwet Bwajni) (1905-1993)

His original name was simply Houphouët. He took his first name, Felix, upon converting to the Catholic Church in 1915, and added the name Boginy—which means irresistible power—when he won his first run-off election in 1945. The name by which he is universally known, however, is his original or middle name, Houphouët.

Houphouët was born in 1905 to an important Boule famil, and inherited a large farm. In 1940 he was selected as the chief of his district, and in 1944 became prominent by helping to organize the Syndicat Agricole Africain (SAA) or African Agricultural Association, the first large organization to protect the rights of Black farmers in Africa.

Within a year the SAA spread throughout the country, and served as the basis for forming the Democratic Party of Côte d’Ivoire (PDCI according to its French name). After the war, France granted rights to its colonial natives, and in 1946, Houphouët was elected to the French National Assembly. In Paris, Houphouët rose to the attention of several successive French leaders, including President Charles De Gaulle. Advancing rapidly in politics, he became the first African to serve as a minister in a European government.

As independence movements spread across Africa, Houphouët led Côte d’Ivoire to independence but, contrary to many other independence movements, advocated maintaining close economic, political, and social ties with France. When independence was achieved in August 1961, Houphouët was elected its first president, and was reelected for the next three decades.

Houphouët’s policy of working closely with France worked out handsomely for Côte d’Ivoire. For the next two decades after independence, Côte d’Ivoire underwent an economic boom.

Ivorians soon had the highest average income in of any non-oil producing African state, with the economy growing by more than ten percent per year. Houphouet was credited with presiding over the “Ivorian Miracle.”

At its height in the early 1960s, Cote d’Ivoire was said to be a model looked to be emulated even by Singapore.

His policy of working with France also paid off well for the French. Between 1961 and 1980, the number of French in Côte d’Ivoire doubled, from 30,000 to over 60,000.

Houphouët’s strategy from the beginning was to build on Côte d’Ivoire’s strongest asset, its agricultural sector, by developing the market for unprocessed agricultural products, namely, coffee, cocoa, palm oil, pineapples, bananas, rubber, cashew nuts, and lumber. However, beginning in the mid-1980s, commodity prices declined, resulting in the end of boom times in Côte d’Ivoire.

Although Houphouët was democratically elected and reelected, was nearest to a king in his single-state. He amassed a huge personal fortune estimated to be approximately $10 bil. USD.

During Houphouët’s presidency, there was little opposition, and few political prisoners. Rather than imprison them, Houphouet preferred to offer lucrative jobs to his critics and opponents. As the approached the end of his life, however, he recognized the need to revive the political process, and encouraged the formation of political parties, which were well in place for the next presidential election after his death.

Although Houphouët was democratically elected and reelected, was nearest to a king in his single-state. He amassed a huge personal fortune estimated to be approximately $10 bil. USD.

He was also able to engage in monumental projects of enormous expense. In 1983 he designated the village of his birth, Yamoussoukro, as the official capital of the nation, and began constructing many buildings and infrastructure at great public expense, such as the Institute Polytechnique and an international airport.

His most luxurious project was the Basilica of Our Lady of Peace, which is currently the largest church in the world, with an area of 30,000 square metres (320,000 sq ft) and a height of 158 metres (518 ft). This was not built at public expense, but was personally financed by Houphouët at a total cost of about USD$150–200 million. Houphouët offered it to Pope John Paul II, as a personal gift. It was consecrated as a Basilica by John Paul II in September 1990.

His most luxurious project was the Basilica of Our Lady of Peace, which is currently the largest church in the world, with an area of 30,000 square metres (320,000 sq ft) and a height of 158 metres (518 ft). This was not built at public expense, but was personally financed by Houphouët at a total cost of about USD$150–200 million. Houphouët offered it to Pope John Paul II, as a personal gift. It was consecrated as a Basilica by John Paul II in September 1990.

At the time of his death in 1993, Houphouët was the longest-serving leader in Africa, and the third longest-serving leader in the world, surpassed only by Kim Il Sung of Korea and Fidel Castro. He also became the most well-known and revered African leader, affectionately known as Papa Houphouët, the “Sage of Africa,” the “Grand Old Man of Africa,” or simply as Le Vieux, “The Old One.”